Sajnbajnu is a Mongolian greeting, which translates into English as: Good day, how are you, are you all right? … You cannot respond to it in the negative. Talking about sadness is considered to bring bad luck. In Mongolia, you have to believe and think positively. As an old Mongolian saying has it: a good thought covers the entire steppe…

Today’s Mongol is the same Mongol as his grandfather and great-grandfather. But time hasn’t by any means stopped here. It continues as it has for hundreds of years in an unchanging rhythm. Maybe the steppe world of the descendants of Genghis Khan simply hasn’t lost its wits yet?

text © Dominika Zaręba

A wide steppe is a man’s happiness

If you want to find out where the real Mongolia is, you have to head for the steppe. “Steppe” here means not only the grassy plains which stretch beyond the horizon in the east and west. It is also the rocky terrain of deserts and semi-deserts intersected by fields of golden dunes and the wild Altai mountain range which extends from the south in a westward direction. The definitions extends likewise to the green hills and valleys of central Mongolia covered with thousands of edelweiss, pasque flowers, bluebells and asters. Even the clearings in the larch forests growing in the taiga in the northern part of the land are covered by this term. The truth about the steppe is in the glistening eye of the Mongol’s galloping short and stocky horse. You look into these eyes and you can tell there’s happiness there. The essence of happiness for the nomad is pride in the wide, limitless expanses and pride in being free. Because freedom means the steppe. It has everything one could ask for. Nourishment – meet and milk from herded animals. Transportation – a strong and hardy horse. Fuel needed to cook up a meal and warm oneself when it is freezing outdoors (since most of Mongolia is treeless, the fuel of choice is dried up cow dung). Last but not least: shelter. A cosy yurt tent, which can be disassembled in a matter of minutes and set up tens or even hundreds of miles further away. Nomads travel freely in search of the best possible grazing grounds for their herds of goats, sheep, horses, cows or camels. The steppe belongs to the Mongolian nation, and the nation belongs to the steppe. A covenant for all time?

The truth about the steppe is hidden in the tenderness of the Mongolian melodies and songs. They are sung here by everyone, and most often you hear them on the bus. Imagine the standard bus, packed to the ceiling with people and goods, rushing across the endless steppe, the sun setting over the distant hills, lighting up grazing herds of horses. Out of nowhere, just like that, the urt-duu steppe song begins to sound. Someone in the back makes a first, timid go at the melody, several people at once join up and next thing you know the entire bus is involved. Like a well-rehearsed orchestra, old and young, women and men sing their musical stories.

– What are the songs about?- I ask Chureł Baatar, whose by far the loudest singer.

– About how calmly life flows on the steppe.

Listen how Urna interprets Mongolian songs

There may not be any centenarians here, but there are thousand-year old words

It may be hard to believe, but the medieval accounts of travelers who saw Mongolia haven’t lost much in terms of their validity. Discovering the world strikingly similar to the one that Marco Polo, Carpine Giovanni da Pian or Wilhelm Rubruk saw has a magic quality to it. Coming face-to-face with the might of the Mongolian tradition brings about unease and awe at the same time. Just like the first European discoverers of Central Asia, we have to – for example – take care not to step on the doorstep when entering a yurt (doing so is a very bad omen) and be sure to flick the first few drops of archi (Mongolian vodka) in the four cardinal directions as a sacrifice.

Noho hor! Silence the dogs! – I shout out as hard as I can as I approach the patterned doors of the yurt standing in the middle of a boundless meadow. And while no ominous bark can be heard, these are the first words you are supposed to holler when paying someone a visit in the steppe. Noho hor is meant first and foremost to make known that weary travelers are approaching, although sometimes it may actually spare you an encounter with a not all too friendly sheepdog. Still absorbed by the fact that this is my first visit to a yurt, I frantically go over in my mind the ‘rules of good behavior’ I read up on before my trip. These rules may well be a thousand years old. How did they go again? All right, the guests all sit on the left hand side. When we’re handed a snack with both hands, we’re supposed to take it with both hands as well. If they pass us food with their right hand and use their left hand to hold up their right elbow, one is supposed to respond by doing the same gesture … My hands are getting all tangled up in the process, while the host family is clearly having a good time looking on as I do my best to keep up with the Mongolian savoir-vivre. Several pairs of black, cheerful eyes are fixed on us. We don’t doubt we’re none the better. We take in their dark hues and sharp facial features. Our gaze settles on the silk dresses of our hostess and her daughters. And so there we are, sitting opposite each other like creatures from two different worlds, not a word is spoken, we communicate with our grins. Two generations of round eyes and four generations of slanting eyes.

This is usually how a first visit to a yurt goes. After that it only gets better. It’s enough to learn a few Mongolian words and expressions to have a nice ‘chat’ about how the sky today is very blue, that you don’t get this kind of wind over in Poland and that my home country is five times smaller than Mongolia but has fifteen times the population Mongolia does. And you can even get used to salted tea with milk. Yes, when you come back to the yurt thirsty and tired after yet another day of traveling in the great outdoors, you can’t think of anything else excepting having a nice bowl of suutei tsai.

Don’t cross the water without asking about the ford

As I sit on a bus, which has gotten stuck in a wide and fast-flowing river with water slowly beginning to pour in through the windows, I remember these words of warning from Mongolian ancestors, and find they are quite ironic, given the situation I’ve found myself in. What’s more, outside is a dark and moonless night. Meanwhile, all the passengers, as if nothing had happened, are calmly moving their bundles from the left side of the bus, which is getting more and more stuck in the muddy water, over to the right side. Little kids nestle comfortably on the armrests of their seats. We’re all – including the driver – waiting for some type of liberator, who maybe will show up and deliver us from our oppression. Well saying it’s oppression is taking it too far – this is a part of everyday life on the roads of Mongolia. Why build bridges, when there are only a few crossings daily, and the river bursts its banks only after a major downpour. Luckily, not far from here there are several yurts and as chance would have it one of the people staying overnight is a driver of a tank truck with gasoline en ruet to the city of Altai. This is just the „emergency road assistance” we need. A few minutes pass and after having this refreshing bath, the bus is ready for the road. I am trying to recollected whether during the two months already spent in Mongolia I have ever come across so much as one Mongol who has lost his cool or shown even the slightest sign of irritation. An old proverb instructs: „if fire burns in your breast, don’t let out the smoke through your nose” and this is the moral code instilled in those for whom the steppe is home. This peace of mind is enviable. For a short moment, you let yourself be charmed by this harmony, rhythm of life, and you inevitably laugh to yourself at the contrasting Slavic impulsiveness and hastiness. But this Mongolian composure and patience is something more than just a trait of character. It’s an entire philosophy and way of life, a way of thinking and perceiving the outside world. In a way, it’s the essence of the entire nomadic culture. A culture so different from our Slavic one it’s pretty much impossible to really have an in-depth understanding and appreciation of it.

Drink airag!

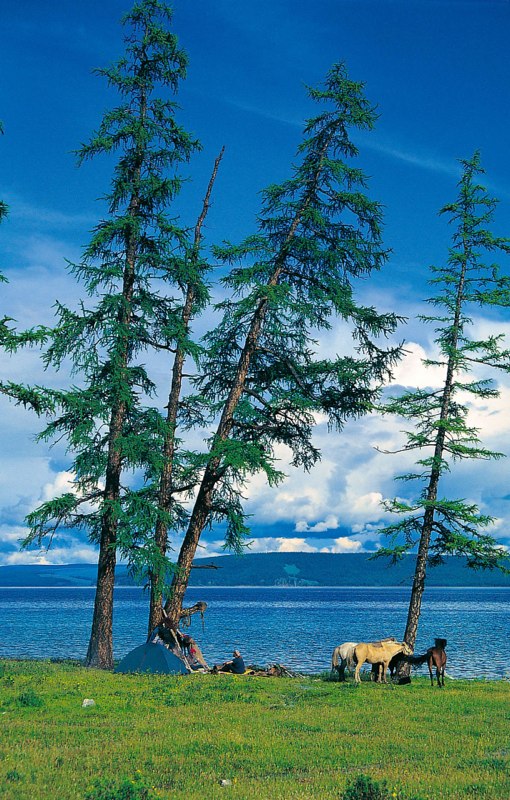

It’s a shame that one can’t have a vivid memory of tastes and smells of the places one travels to. Were this possible, one could not only show photographs but share with others the mysterious smell of the herbs on the meadow next to the shore of Lake Khövsgöl where we set up camp after another day of really pushing our Mongolian horses. Or the smell of soup cooked up on the fire by Gambataara – our guide – with some wild chives picked up along the way. Or the taste of tea brewed in water from the cleanest lake in the world…

But the number one taste in the world of the descendants of Genghis Khan is airag, otherwise known as kumys, or fermented mare’s milk. Airag is a cure for everything – says Baasan, an older professor and our companion to the far-away lands of the Mongolian Altai region. And his opinion sounds authoritative. If your stomach’s giving you problems, if you are suffering from headache, you are having trouble falling asleep, you’ve lost your appetite – drink airag! Sounds like a cool advertisement. It doesn’t take much to convince us. We are just finishing the second cup’s worth of this milky drink. A short, 20 minute break before we continue on our journey. I’ve lost track of how many breaks we’ve had. The bus driver along with the passengers have just decided that it’s high time for a refreshing bowl of kumys. We stop at the first available yurt and are in the process of ‘healing’ our poor stomachs, which are all shook up after a particularly bumpy road experience, with some airag. Airag taste a bit like kefir, except it’s a bit more tart, and in some regions of the country, slightly bitter. Everyone drinks it here, small children included, even though it has slightly over 2% alcohol. The mare is milked a few times a day, with the foal kept close to its stomach. The caring mare will allow herself to be milked only when it feels the presence of its own nearby. The milk is poured into leather sacks and mashed until it begins to froth. After fermenting overnight it’s ready to drink. You can never refuse kumys when it’s offered to you. Doing so would be like holding the ancient history of the Mongolian nation in low regard. Who knows, maybe the strength of this tradition is hidden in mare’s milk?

Once you get to drinking kumys in Mongolia, you’re treated as one of your own, all barriers and cultural differences break down. In one small bowl of mare’s milk you can find a piece of the Secret History of the Mongols along with a sense of the wild and primeval nature and a gust of the wind, which long, long ago founds its home in the steppe.

English translation: Piotr Szmigielski